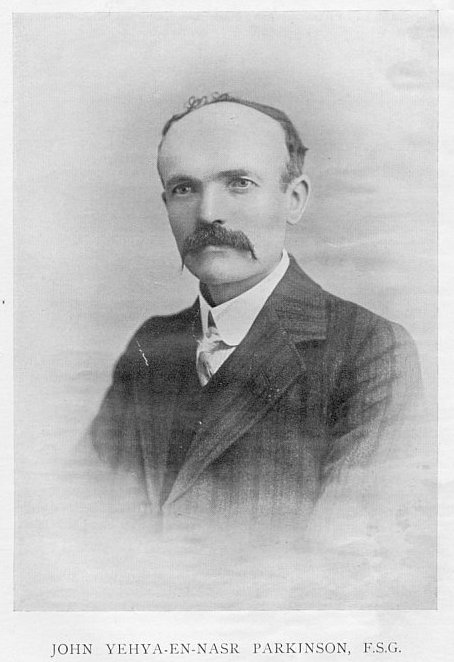

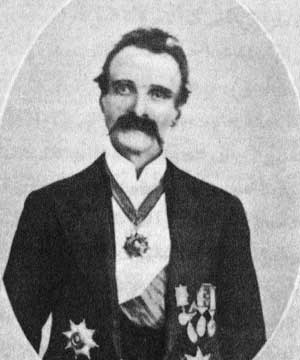

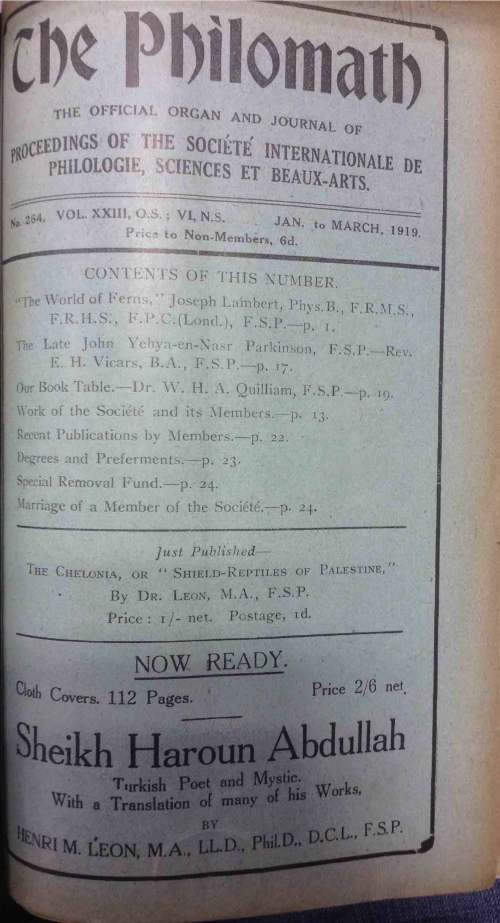

Today I received a rarity in the post that was published exactly a hundred years ago: a translated selection of the Ottoman Mevlevi Sufi poet Sheikh Haroun Abdullah’s (c.1556-c.1641) poems by Abdullah Quilliam. Quilliam had it privately published in 1916 under the pseudonym Henri M. Léon that he adopted on his return to England, c. 1909-10. [1] It was dedicated to his daughter, May Habeeba Quilliam, who had died at the age of eleven in May 1908 from diphtheria. [2] The volume was a matter of nostalgia for Quilliam as the translations had been undertaken on those occasions when he had been in Istanbul between 1903 and 1908:

in attendance upon His Imperial Majesty Ghazi Sultan Abdul-Hamid Khan, at the Palace of Yildiz, and form, to me, a souvenir of the many kindnesses I experienced at the hands of my then Imperial Patron, for whom I shall always cherish feelings of affection, gratitude, sympathy and respect. [3]

The introduction which introduces the reader to Sufism in general, the Mevlevi Order, and to Sheikh Haroun’s life and works was composed the following year in 1909, ‘after the [Young Turks] Revolution’, ‘during the time I was living in retirement at Bostandjik’ (which is on the Asian side of modern-day Istanbul). [4] The introduction is crisply written and is, like the book as a whole, evidence of Quilliam’s knowledge of and attachment to Sufism. Here is an example of Quilliam’s felicitous writing on the subject:

The annihilation of self, the entire consecration of the mind and body to the service of Allah, the contemplation of the Divine, and the disregard of the earthly, such is the tariq, the path, by which the Dervish seeks to consummate his union with the One. Everything speaks to him of the Beloved, the Unity. But the mere perception of the Immanence of the Divine, is only the first step in the Way. The End of the Path is only to be attained when the conscious union with the Divine is obtained. The veil which material Nature has placed between the self-knowing part, the Ruh [Soul], and Allah ta’ala must be pierced. The mind must be emptied of all images, of all worldly thoughts, fears, longings, or aspirations, and brought to a realization of the Presence. Then and only then does the nafs [Spirit] find itself alone with Allah. [5]

Was this interest in Sufism more than merely a scholarly one for Quilliam? Was he a member of a Sufi Order? We simply do not know presently. However, two possibilities suggest themselves. Quilliam’s patron, Abdul Hamid, was himself a Shadhili and a devoted follower of Sheikh Muhammad Zafir al-Madani (1828–1903), who taught the Way at the Yildiz Hamidiye Mosque. Abdul Hamid built Ertuğrul Tekke Mosque for his sheikh and the Shadhili Order in Yildiz district, just below his palace, which was completed in 1887. When I visited the tekke in 2008, I was shown the intricately carved lectern and architectural backdrop that Abdul Hamid, trained inter alia as a master carpenter, had carved for his sheikh. Besides the Shadhilis, another possible tariqa that might have been attractive to Quilliam was the Mevlevi Order itself as his dedicated interest in Sheikh Haroun Abdullah indicates. Further research is definitely needed into whether or not Quilliam might have joined a tariqa at any point during his time in Istanbul, the Ottoman territories or Morocco.

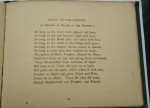

Let me end by presenting Quilliam’s felicitous translation of Sheikh Haroun’s ghazal in praise of the Prophet:

So long as the heart doth pulsate and beat,

So long as the sun bestows light and heat,

So long as the blood thro’ our veins doth flow,

So long as the mind in knowledge doth grow,

So long as the tongue retains power of speech,

So long as wise men true wisdom do teach,

The praise of God’s Prophet, Ahmed the Blest,

Shall flow from our lips and spring from our breast,

‘Twas Rasul-Allah from darkness of night

Did lead us to Truth, did give to us light,

Did point out the path, which follow’d with zest,

Leadeth to Islam and gives Peace and Rest,

Praise be to Allah! ‘Twas He who did send,

Ahmed Muhammad, our Prophet, our Friend. [6]

Notes

[1] Henri M. Léon, Sheikh Haroun Abullah: A Turkish Poet and His Poetry (Blackburn: Geo. Toulmin & Sons for La Société Internationale de Philologie, Science et Beaux-Arts, London, 1916), 108pp; Ron Geaves, Islam in Victorian Britain: The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam (Markfield: Kube Publishing, 2010), p.259.

[2] Léon, Sheikh Haroun Abdullah, p.5; Geaves, Islam, pp.112, 259.

[3] Léon, p.11.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p.15, with some corrections to the Arabic transliteration. The translations of Arabic terms that are placed in square brackets are taken from Quilliam’s own glossary at the end of the book to preserve his own understanding of these terms.

[6] Ibid., p.81.

There are a lot of things that could be said about the

There are a lot of things that could be said about the